Leading Snowflakes|Engineering Manager Handbook Insights for Effective Team Leadership

Discover key strategies from Leading Snowflakes to overcome engineering management challenges, boost team productivity, and foster innovation with proven leadership techniques.

This post was translated with AI assistance — let me know if anything sounds off!

Table of Contents

Leading Snowflakes — Reading Notes

“Leading Snowflakes The Engineering Manager Handbook” — Oren Ellenbogen

As a new manager, everything felt confusing; my knowledge of management was limited to compiling previous work experiences, observations, or casual chats with colleagues. I knew which actions by supervisors were positive and which were negative from the perspective of their subordinates. That was about all I had—fragmented knowledge without a systematic concept. So, I started reading books and began recording each author’s experiences. When encountering similar situations, having this “knowledge confidence” helped me avoid panic.

Leading Snowflakes

Please provide the Markdown paragraphs you want me to translate into English.

Author: Oren Ellenbogen

Publication Year: 2013

Thanks to 海總理 for the recommendation

The author has spent nearly 20 years progressing from a software engineer to management roles. He has served as a Technical Lead and Engineering Manager in both large corporations and startups. This book clearly outlines the challenges engineers face when moving into management and the methods to organize and solve them.

I find it very similar to my background, both originally in software development and just starting in management; the key points mentioned in the book taught me many practical methods!

- This article is a personal note combined with some personal opinions. In this age of fragmented information, it is highly recommended to read the original book yourself to systematically grasp the core ideas.

- The purpose of notes is to make it easier to quickly locate points you want to review later.

- Some content is directly quoted from the original text.

Lesson 1. — Switch between “Manager” and “Maker” modes

Transition from Engineer (Maker) to Manager

Completing tasks well and elegantly solving problems are measures of an excellent engineer, but as a manager, the evaluation is not based on the ability to complete tasks. We have already proven this. Instead, the standard is leading, driving, and improving the team’s capabilities and goals.

However, you cannot completely detach yourself from the task, as fully disconnecting from the task details may lead to losing connection with team members, which poses significant long-term risks to execution results, priorities, and trust.

So being a manager doesn’t mean you don’t do engineering tasks; rather, you need to engage in both. It’s about finding the right balance between being an engineer (Maker) and a manager (Manager).

As engineers, we like to have uninterrupted time to stay in context and solve difficult problems; but as managers, we need to frequently step out to help the team and care for teammates, so being interrupted is actually part of a manager’s job.

But we also need to be both engineers and managers. What should we do?

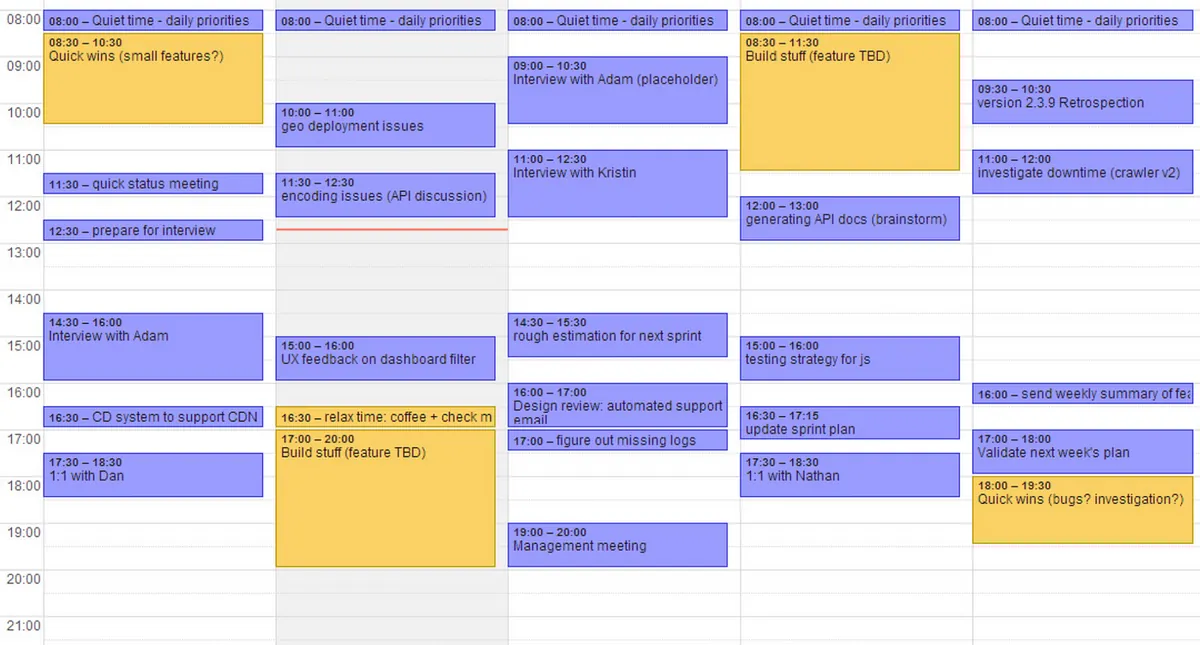

The author suggests creating two Calendars: one as Maker (engineer) and one as Manager. Every morning, spend 15–30 minutes organizing your thoughts, planning the day’s schedule, deciding what tasks to do, what meetings you have, and identifying continuous free time slots to tackle tasks (as Maker).

Author’s Calendar Template

We also need focused time

The author states that although we are now managers, we still need to handle tasks; the available focus time during gaps is more important to us than before.

The author mentions that you can use certain actions to signal your teammates during focused times, indicating “Please do not disturb me for now!”

Methods include: going to the conference room, wearing headphones, or even buying an ON AIR! switch light to place on the desk.

If it’s not an urgent issue, you can ask your teammates to leave comments or compile information in an email for you to handle after your focused work time.

Assessing Tasks You Can Complete as an Engineer Within Your Available Time

Since I can no longer focus solely on development tasks like when I was purely an engineer (Maker), I need to choose tasks that I can personally execute based on the available time in the engineer’s schedule.

Do not become the technical bottleneck of the team. Our mission is to enhance team capabilities, explore new technologies, and broaden the company’s internal and external technical perspectives. Possible tasks include researching technical issues in advance, sharing findings with teammates and letting them execute, resolving company technical debt, improving processes to boost development efficiency, adopting new technologies, open-sourcing company technology, providing open APIs, hosting external hackathons, and more.

The Most Important Thing Is Balance

The author suggests starting with a 15–20% ratio. Originally, it was 100% as Maker, but now it could be 20% as Maker / 80% as Manager (depending on the actual team size and member capabilities; the author also mentions 50% / 50% is possible). The key point is not to spend 100% of the time on engineering development but to invest more effort in management.

Make Good Use of 1:1

Regularly hold 1:1 meetings with teammates to give mutual feedback and share what you have learned.

If managerial tasks consume all your time

The author finally mentions that if you manage too many tasks and cannot do engineering work (as a Maker), or if you feel disconnected from tasks and technology, consider working from home a few days a week to isolate from the company or participate in hackathons.

Lesson 2. — Code Review” Your Management Decisions

Regularly review the decisions you make as a manager.

As engineers, we have many methods or tools to improve our skills by following them, such as pair programming, code review, and design patterns; but as managers, especially beginners, we often feel quite lonely.

We don’t want to admit our ignorance about superiors or subordinates, fear taking responsibility for the team’s success, or worry about balancing technical (debt) and business needs.

The author mentions stepping out to seek ways to improve management skills, openly requesting feedback, and enhancing management abilities; being as passionate about managing as when working as an engineer.

Record & Review Decisions

Colleagues and bosses are powerful resources we often underestimate. We can quickly learn from their feedback; establishing good records and reviewing decisions regularly helps us receive better feedback.

The author mentioned:

“There is no one right way, there are only tradeoffs.”

I think so too. If it weren’t a dilemma, you probably wouldn’t ask me; asking means your teammates don’t know how to decide.

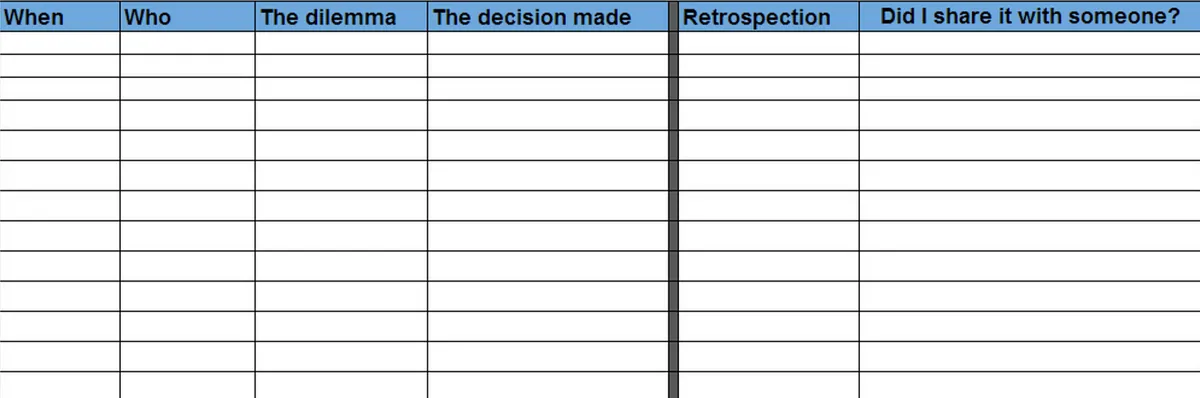

We can list the options and provide decisions to teammates, but at the same time, we must record the decisions made.

Template of the Record Sheet Provided by the Author

Develop the habit of keeping records, and make sure the content can be recalled later.

The author suggests reviewing monthly and sharing the discussion and decisions with your boss, other managers, or colleagues (at least half of the issues). Listen to others’ opinions; anonymity can protect the individuals involved, focus on the issue, not the person, and keep a record.

Key Points for Retrospective Review

About the Issue:

How many technical issues does it cause?

Is it a personal issue?

Is it just an individual member’s isolated issue? (Is it simply that they don’t understand the goal?)

Does this issue occur repeatedly in other teams as well?

About Decision Making:

Does this issue really need to be decided by the manager?

Have you asked your teammates for their suggestions?

Is there anyone more experienced who can offer advice?

Would you make the same decision if you reconsider now?

Lesson 3. — Confront and challenge your teammates

Encourage teammates to step out of their comfort zones while avoiding becoming a jerk or falling into traps.

The author mentioned that at first, he was very uncomfortable because a friend who was once a colleague became his subordinate. He feared damaging their original relationship, so he took on all the finishing tasks by himself. However, he eventually realized that the more he tried to protect the relationship, the more distant he became from his teammates. His constant solitary hard work and lack of sharing caused his teammates to lose confidence.

Looking back, the author says that instead of fearing hurting teammates’ feelings, it’s better to speak your true thoughts. The fear of “hurting teammates” is simply a selfish imagination and unnecessary. Moreover, as a manager, it is your responsibility to lead the team forward and grow; you must have a broad perspective and control risks.

Sharing honest thoughts is difficult for both parties, but it is the responsibility of a manager.

We need to show empathy, not sympathy. To help them truly excel in their work, they need our objective feedback.

The author provides the following three points to help us balance emotions and behavior:

Did I show empathy?

Yes, you have clearly stated your expectations.

Have I led by example?

“If you want to achieve anything in this world, you have to get used to the idea that not everyone will like you.”

If you want to achieve something, you must get used to the fact that not everyone will like your ideas.

Four Common Pitfalls:

Compared to hiding, have I openly shared my failures? (This can be through writing articles or emailing everyone)

Forget to summarize discussion results (get used to recording 1:1 and discussion outcomes)

Using the wrong feedback medium, failing to identify the real issue (find the appropriate feedback channel based on team culture, e.g., 1:1)

Delayed Feedback

We need to recognize that engineers enjoy challenging themselves and improving their skills, while also wanting respect and feedback from their supervisors. Our mission is to lead the team’s growth, so we should not delay whenever there is an opportunity to give feedback. Not making a decision is also a decision. Moreover, once the culture of feedback weakens, it becomes even harder to reignite.

Summary

Can take time to write down ways to motivate teammates and ask the supervisor if they are being too protective of the teammates?

Lesson 4. — Teach how to get things done

How to complete tasks with lower risk.

Leading by example is a good approach. Occasionally participate in the team’s development to demonstrate how to plan and produce quality features that convey our ideas. Also, focus more on explaining the Why? (why we do it this way) and less on the How? (how to do it).

The author mentions that a highly transparent culture provides team members with complete context, enhancing their ability to drive decisions.

Reduce Risk

To reduce production risks, the author suggests breaking down requirements into many small iterative features and sharing this idea with other teams.

Scale and performance — always have a backup plan

Will this feature affect performance (or cause other issues)? Can it be known in advance? Is there a backup plan (toggle)? If there is no backup plan, it’s better not to implement it, as it can affect team confidence.Break tasks into smaller sub-tasks to reduce deadline risks

It may be difficult at first, but it can be trained and learnedLeverage Peer Pressure

Divide tasks among teammates for joint collaboration, working together to achieve goals (Code Review is also part of this).Continuous Internal and External Communication

Internal: Ensure expectations, synchronization, deadlines, and resources.

External: Communicate clearly; if time is tight, cancel unimportant meetings.Support, Bug Fixes, Documentation

It’s not enough to just release features; you also need to provide good customer support, fix bugs, and maintain documentation.Conduct thorough reviews and delegate tasks to provide others with leadership opportunities

Select a few tasks that can lead by example

Ask teammates about what they have learned, what motivates them to be more proactive, and what they dislike.

Lesson 5. — Delegate tasks without losing quality or visibility

Delegate tasks without losing quality and visibility.

As a manager, it is essential to delegate tasks properly. The author believes delegation should involve setting clear expectations and trusting that the assigned team members have the ability to execute, the opportunity to learn, and the space to make mistakes. On the other hand, managers must also protect their team members from pressure coming from the company.

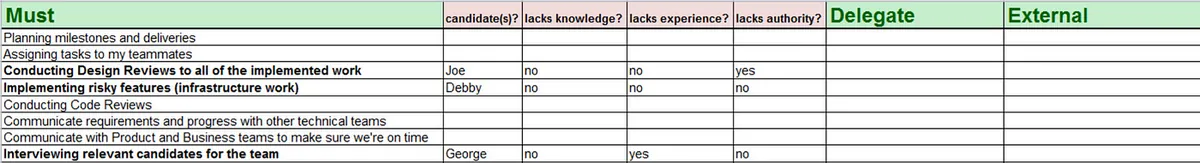

The author used the following table for recording:

This section mainly records tasks important to team goals; daily work does not need to be recorded.

- Must write down the task content

Regarding whether to delegate a task to teammates, the author first asks if the task can only be done by themselves and if it is something a manager should handle. The second question is whether the task is a long-term leadership responsibility; if neither is true, the task is delegated to teammates.

For tasks to be delegated, evaluate teammates’ experience and skills to find the right candidate.

External Resources or Expected Resources Above (Feedback/Tool)

Delegate

For the Delegate section, we can provide a one-page paper explaining our expectations and a simple example.

Lesson 6. — Build trust with other teams in the organization

Teamwork and seamless collaboration between teams.

The author explains that organizations split into many small teams to enable faster decision-making and handle more tasks; defining each team’s direction is actually easy (e.g., iOS team focuses on iOS apps), but aligning the goals of all teams is the difficult part.

The more groups there are, the harder it is to unify everyone’s values, expectations, priorities, and implicit assumptions.

Focus on the reasons and motivations for splitting the team rather than the output; otherwise, it may lead to conflicts.

The author suggests the following methods to align the directions of each team:

The team should have a vision, not just complete tasks well.

Managers need to distinguish between needs and wants.

Optimize the team to complete the right tasks faster, not just more tasks.

Establish Good Communication with Other Team Managers

The author suggests sharing your team’s status, obstacles, challenges, upcoming main tasks, and their reasons during the biweekly managers’ meetings.When there is a difference in priority opinions with other teams, you can explain by bringing up other factors (e.g., completing this task can reduce customer service complaints, provide a one-time permanent solution, or create a synergistic effect…).

First, understand where the external team needs our help and proactively follow up closely.

Next, we present the points where our team needs help from external teams.

Make a checklist to confirm all points are discussed during the meeting; if not, follow up with relevant managers afterward to explore other possibilities.

If it is not possible, weigh the potential delay or alternative solutions, and inform stakeholders to prevent behind-the-scenes complaints.

Everything Is a Trade-off

Here are 5 more ways teammates can build close relationships with other teams:

Simple Thank You Letter (Appreciation for Assistance)

Exchange Team Work

Internal Tech Annual Meeting, Sharing with Each Other

Observe user behavior together and brainstorm optimization ideas collaboratively

Invite a teammate from another team to join our work

Summary

“Imagine that someone from Team A drops a feature that Team B needs due to an urgent support issue. Without communicating this priority change to Team B, trust will decrease even if the priority change is justified.”

「 difference between transactional trust and relational/emotional trust 」

Understand Transactional Trust and Relational Trust.

Transactional Trust — Whether people will keep their promises and complete tasks

Relational Trust — Whether people act in ways that build and protect relationships

Lesson 7. — Optimize for business learning

Building a business learning culture instead of just creating a culture, optimizing throughput, and optimizing value.

Premature Optimization Is a Disaster

Focus on solving current problems, not optimizing for the sake of optimization.

Even if we are not responsible for the entire project, we can still optimize internal operations. Major successes often come from the accumulation of small improvements.

As managers, we must demonstrate the motivation behind our decisions

Establish a business learning (value) culture and build a culture (the focus is not on creating solutions, but on the business problems we aim to solve)

Optimization of Efficiency vs Optimization of Throughput:

Optimization of Efficiency: Reducing the time to complete a single task

Optimization of Throughput: Increasing the number of tasks completed within a time period (e.g., a quarter)Know the impact of each optimization,

The Importance of Automation (Save Time Once and for All)

Optimize Value Using the AARRR Principle:

Acquisition: How to attract more users

Activation: How to guide users to complete tasks that help them understand the product’s value (e.g., Alarm App, onboarding users to set up an alarm)

Retention: Increase return visits and usage frequency

Referrer: Let your users and content bring more traffic

Revenue: Digitally assess the revenue generated by users

These five items are closely related. If Retention is low, you might consider adjusting Referrer and Acquisition simultaneously.

As engineering managers, our role is not to bury ourselves in coding or focus solely on technology; we should periodically realign with the product’s value.

When the product is still in the early market testing phase, the focus should be on optimizing efficiency (quickly completing tasks) by repeatedly following this process:

Features can improve retention -> Release features -> Learn -> Adjust & repeat.

Evaluate areas for improvement at each stage from feature assessment to release (spending too much time on design? On discussions?)

Can you invest 20% of the time to reduce 80% of the development time? Especially the painful parts.

Can we first experiment or release it to a minimal audience? This avoids having a large feature set that ends up unused.

- To effectively track data, you must understand the results of your efforts

“If you can’t make engineering decisions based on data, then make engineering decisions that result in data.”

Although “the company will fail without this feature” is certainly more alarming than “this feature will cause technical debt,” as managers, if we can secure more time to address technical debt, we should do so. We must ensure proper communication and control.

Optimizing code that may never be used is not very meaningful.

After the initial trial phase, the product model becomes stable; this is the right time to optimize throughput (e.g., given X resources, achieve Y output).

Provide business requirements predictability (as above)

Track team output (e.g., “01/01/2013–14/01/2013: 2 Large features, 5 Medium features, 4 Small”), and use long-term statistics to provide forecasts.

Identify & Solve Bottlenecks:

Synchronous communication: For example, in the product development process, design resources are needed. When entering the engineering development phase, do we already have clear specifications to proceed with development? Or are we still waiting? Is there anything we can do in the meantime?

Infrastructure: Making Code Scalable and Maintainable

Automation: Use automation to handle tedious manual tasks, saving time and reducing errors

Because business strategies constantly change, we should maintain a more open and flexible mindset toward optimization strategies. The summary of optimization should still focus on business needs.

Lesson 8. — Use Inbound Recruiting to attract better talent

About Recruitment.

You should start doing the following tasks regularly. If you wait until suddenly lacking talent, you will have to rely on traditional recruitment methods, conducting endless interviews but still struggling to find the right candidates.

Internal:

Cultivate a good engineering culture environment (e.g., Code Review, annual meetings…)

Create an Attractive Work Environment

Manage it like a brand

Team Members Collaborating

Strengthen human connections (e.g., birthday celebrations)

First, make members feel proud of the team

External:

The internal team regularly answers community questions weekly (e.g., Stackoverflow, etc.) to increase exposure.

Hiding recruitment Easter eggs in code (e.g., Web Developer Tools)

Sharing with the community the problems our team encountered and the solutions we found (Article or Talk)

Hosting a hackathon

Creating a side project (e.g., Open Source Project)

Assign the above tasks to team members so everyone can contribute to finding great talent together.

Lesson 9. — Build a scalable team

Building a scalable team.

Building scalable software was our previous responsibility as engineers, but now the challenge is to create a scalable team.

Unlike programs, people have expectations, needs, and dreams to consider.

The author wants to create a happy work environment where teammates understand the expectations of tasks and face new challenges; and to maintain this passion continuously.

Aligning Goals

Align personal vision with company goals. Without understanding the current company objectives, team dysfunction is likely to occur.Aligning Core Values

It is a consensus and tacit understanding about ways of working and what is important; team core values are not fixed and should evolve with the times.Balance

Assign different visions, autonomy, and ownership according to team members’ roles and growth; collaborate and grow together (e.g., newcomers expect to understand company workflows, veterans handle code reviews and mentoring); everyone should have opportunities for growth.The core values of the group outweigh those of the individual.

This may lead to some people leaving and requires patience and time to achieve; there are also many challenges (e.g., when someone leaves, they may question the core values).Achievement

Results should bring a sense of achievement. As a manager, you must not let your team lose their enthusiasm.

Practice

Define the team vision

EX: The author’s team works on web crawling, and their team vision is “To build the largest, most informative profile-database in the world.”

Please note this is a vision, not a short-term goal or something they don’t want to do.Define Core Team Values

When selecting core values, ask yourself, “Is this value so important that someone would be fired for lacking it?”

Write down the core values and their reasons.

The author provides the following core values he wrote:- Do not let others (other teams) clean up the mess; the team must take responsibility for its own mistakes.

- Maintain loyalty and respect toward all team members.

Having core values provides clearer criteria for recruitment and dismissal, and sets a standard for how to work.

Define Members’ Expectations of the Team and Managers

Provide a productive and happy work environment

Understand the Why of a Task, Not the How

Receive genuine feedback

Opportunity to lead other members

Able to share work results

Define Expectations for Team Members

Basic Expectations:

Task completed

Maintain a passion for learning

Keep the passion for sharing and teaching

Understand the bottom line of doing things sensibly

Personal Expectations:

Set Expectations According to Capability

Able to Train Others to Adapt

Promote Change Instead of Complaining

We are a team. Each member has their own responsibilities and deliverables, while also collaborating with others, helping each other, and growing together. Defining expectations is like a contract; under the shift from colleague relationships to managerial ones, it enables better and more purposeful leadership. Defining these items is not easy and requires time and patience to iterate.

“You can’t empower people by approving their actions. You empower by designing the need for your approval out of the system.”

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to contact me.

This post was originally published on Medium (View original post), and automatically converted and synced by ZMediumToMarkdown.